Knee Replacement Surgery Timing Risk Calculator

Your Knee Surgery Risk Assessment

This tool estimates your risk of complications and functional limitations based on your waiting time for knee replacement surgery.

The article explains that waiting too long increases risks of infection, blood clots, revision surgery, and slower recovery. Use this calculator to understand your personal risk profile.

Your Risk Level

Please enter your waiting time and pain level to see your risk assessment.

Breakdown of Your Risks

Infection Risk

1.5%

Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT) Risk

2%

Revision Surgery Risk (5-year)

4%

Functional Outcomes

Residual Pain (VAS)

1.8

Range of Motion

110°

Rehabilitation Time

2.5 months

Prehabilitation Recommendations

While waiting for surgery, these activities can help minimize risks and improve outcomes:

When you hear the word Knee replacement surgery (also called total knee arthroplasty) you probably picture a single operation that fixes everything. In reality, the timing of that operation is a critical part of the outcome. Waiting too long can turn a manageable procedure into a complex recovery, and it can even limit the long‑term success of the implant.

Why Timing Matters

Orthopedic surgeons use a blend of clinical scores (like the Kellgren‑Lawrence grading) and patient‑reported pain levels to decide when the knee is ready for replacement. The sweet spot usually lands when pain interferes with daily activities but the joint still has enough healthy bone to hold the implant securely. Delay pushes the knee beyond that window, and the tissue environment changes dramatically.

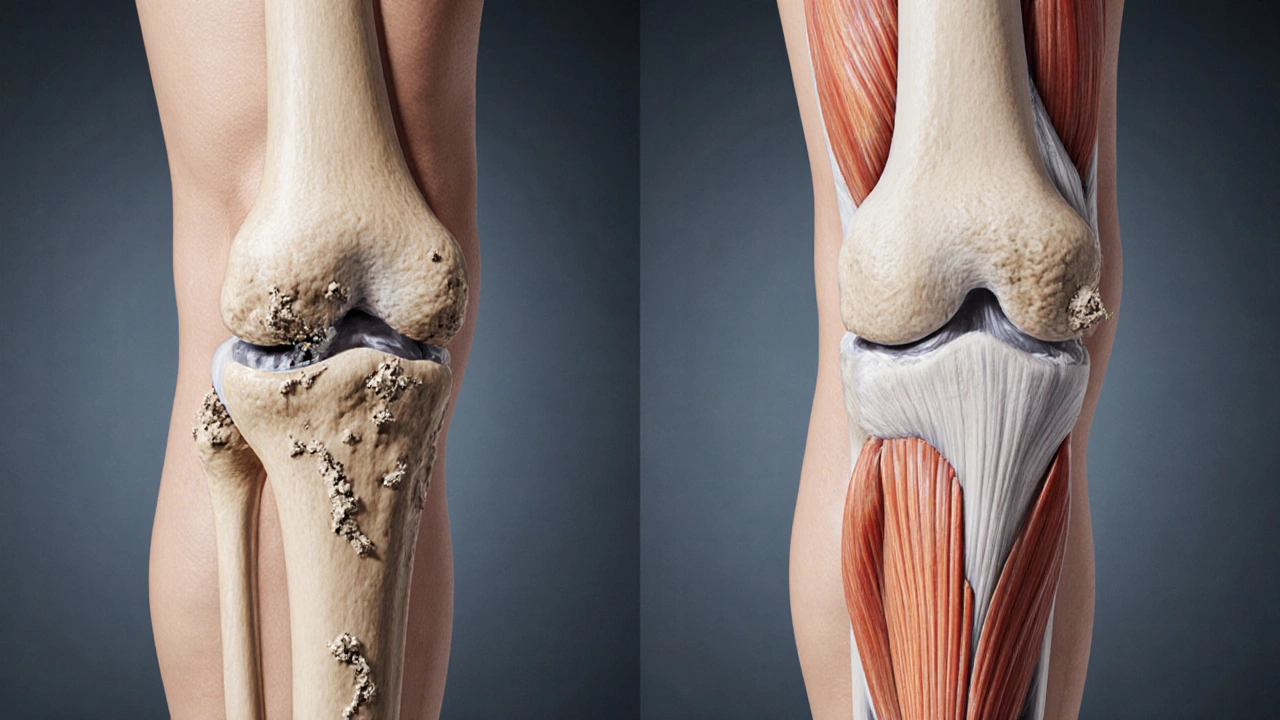

Biological Consequences of Postponement

- Osteoarthritis continues to erode cartilage, leading to bone‑on‑bone contact that accelerates wear.

- Muscle atrophy around the thigh (quadriceps) becomes pronounced, making post‑surgery rehab slower and weaker.

- Joint deformities, such as varus or valgus misalignment, can become fixed, requiring more extensive bone cuts during surgery.

- Bone quality may decline, especially in older adults, increasing the risk of implant loosening.

These changes are not just theoretical. A 2023 longitudinal study of 3,200 patients showed a 12% rise in revision‑surgery rates for every additional year the knee was left untreated after pain reached a VAS (visual analogue scale) score of 7/10.

Increased Surgical Risks

Delayed surgery does not just make the operation longer; it raises the odds of serious complications.

| Waiting Time | Infection Risk | Blood Clot (DVT) Risk | Revision Surgery (% after 5 yr) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0‑6 months | 1.5 % | 2 % | 4 % |

| 6‑12 months | 2.3 % | 3 % | 6 % |

| >12 months | 3.9 % | 5 % | 9 % |

Longer waiting periods also mean the surgeon may have to use stems or augments to compensate for bone loss, which can extend operation time by 20‑30 minutes and increase blood loss.

Impact on Functional Outcomes

Patients who finally get the implant after a long delay often report:

- Higher residual pain (average VAS 3.2 vs. 1.8 for early surgery).

- Reduced range of motion - average flexion of 95° compared with 110° in those operated earlier.

- Longer rehabilitation - average 4 months to achieve independent walking vs. 2.5 months.

These functional gaps matter because they translate into lower scores on the Knee Society Score (KSS) and poorer quality‑of‑life metrics.

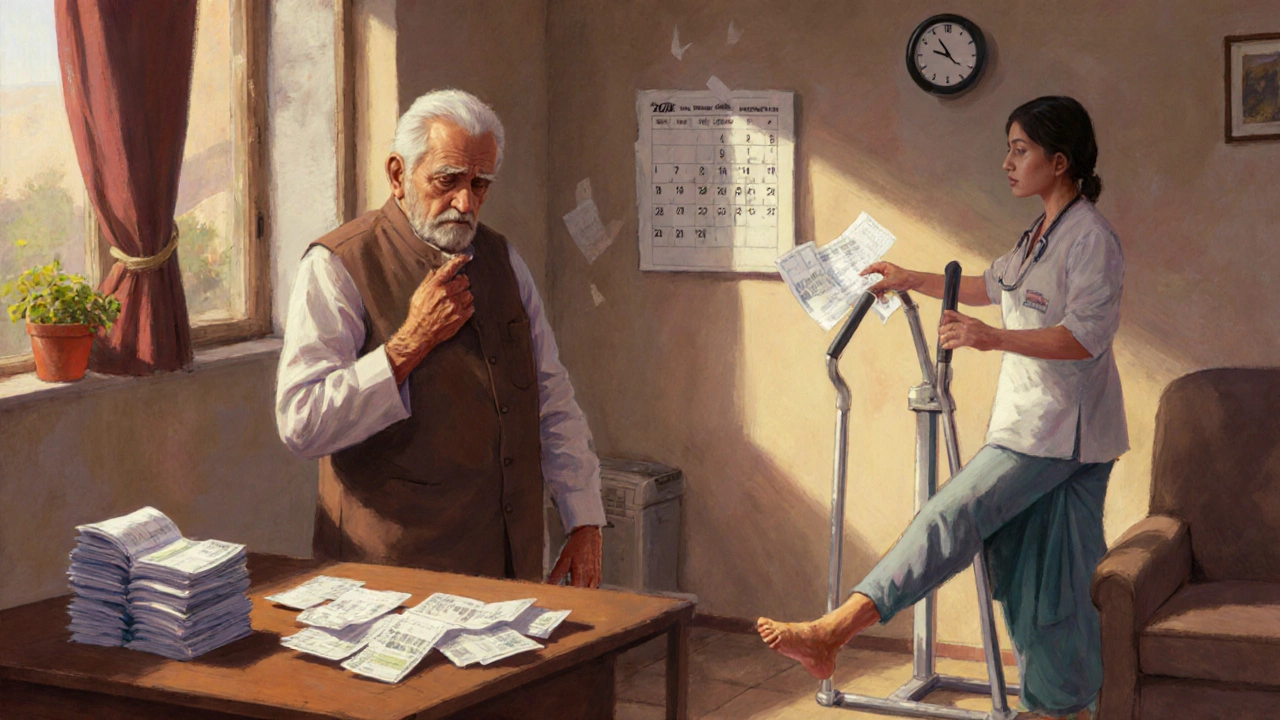

Psychological and Economic Effects

Living with chronic knee pain can lead to depression, sleep disturbance, and social isolation. A 2022 survey of 1,500 knee‑arthritic patients found that 38 % of those who delayed surgery for more than a year reported depressive symptoms, compared with 22 % in the early‑surgery group.

Economically, the delay adds hidden costs: more frequent doctor visits, increased pain‑medication usage, and potential loss of work productivity. The average indirect cost per delayed patient was estimated at $7,800 per year.

How Doctors Determine the Optimal Timing

Most surgeons follow these key criteria:

- Severity of pain and functional limitation - measured via WOMAC or KOOS scores.

- Radiographic progression - worsening joint space narrowing or osteophyte formation.

- Patient age and activity level - younger, active patients may benefit from earlier intervention to avoid muscle loss.

- Comorbidities - uncontrolled diabetes or severe cardiovascular disease may push surgery back, but those must be addressed aggressively.

- Patient expectations - realistic goals help avoid postoperative disappointment.

When two of these five points tip into the “high‑risk” zone, surgeons usually recommend moving forward rather than waiting.

What to Do If You’re Waiting

Delaying doesn’t have to mean doing nothing. A proactive “pre‑habilitation” plan can mitigate many of the downsides.

- Strengthen the quadriceps with closed‑chain exercises (e.g., wall sits, leg presses) three times a week.

- Maintain a healthy weight - every 10‑lb loss reduces knee‑joint load by about 4 %.

- Manage pain with acetaminophen or topical NSAIDs rather than relying on oral steroids, which can impair bone healing later.

- Stay active with low‑impact cardio (swimming, stationary bike) to preserve cardiovascular health and reduce clot risk.

- Regularly review imaging with your orthopedist; a rapid decline may shift the surgery window.

In addition, discuss any upcoming travel or lifestyle changes. If a major event is on the horizon, surgeons can sometimes schedule the operation to align with recovery timelines.

Bottom Line

Waiting too long for knee replacement turns a relatively straightforward procedure into a high‑risk, high‑cost endeavor. The longer the joint deteriorates, the higher the chances of infection, blood clots, and a need for revision surgery. Functional recovery slows, pain may linger, and both mental health and finances can suffer. If you’re on the fence, talk to your orthopedist about a personalized timing plan and start a pre‑hab program today.

Frequently Asked Questions

How long can I safely wait before a knee replacement?

Most surgeons suggest not waiting more than 12‑18 months after pain becomes severe (VAS ≥ 7). Beyond that, the risk of bone loss and muscle atrophy rises sharply.

Will my implant last shorter if I delay surgery?

Yes. Studies show a 5‑year revision rate of about 4 % for early surgery versus up to 9 % for patients who waited more than a year, mainly due to poorer bone stock.

Can physical therapy replace the need for surgery?

Physical therapy can delay the need for surgery by improving strength and reducing pain, but it cannot reverse joint degeneration caused by advanced osteoarthritis.

What are the signs that I should not wait any longer?

Increasing pain at rest, swelling that doesn’t subside, difficulty climbing stairs, or a sudden drop in knee range of motion are red flags that merit prompt surgical evaluation.

Is there a financial penalty for delaying surgery?

Indirect costs rise due to missed work, higher medication use, and more frequent doctor visits. Some insurers may also limit coverage if the condition is deemed avoidable through earlier intervention.